|

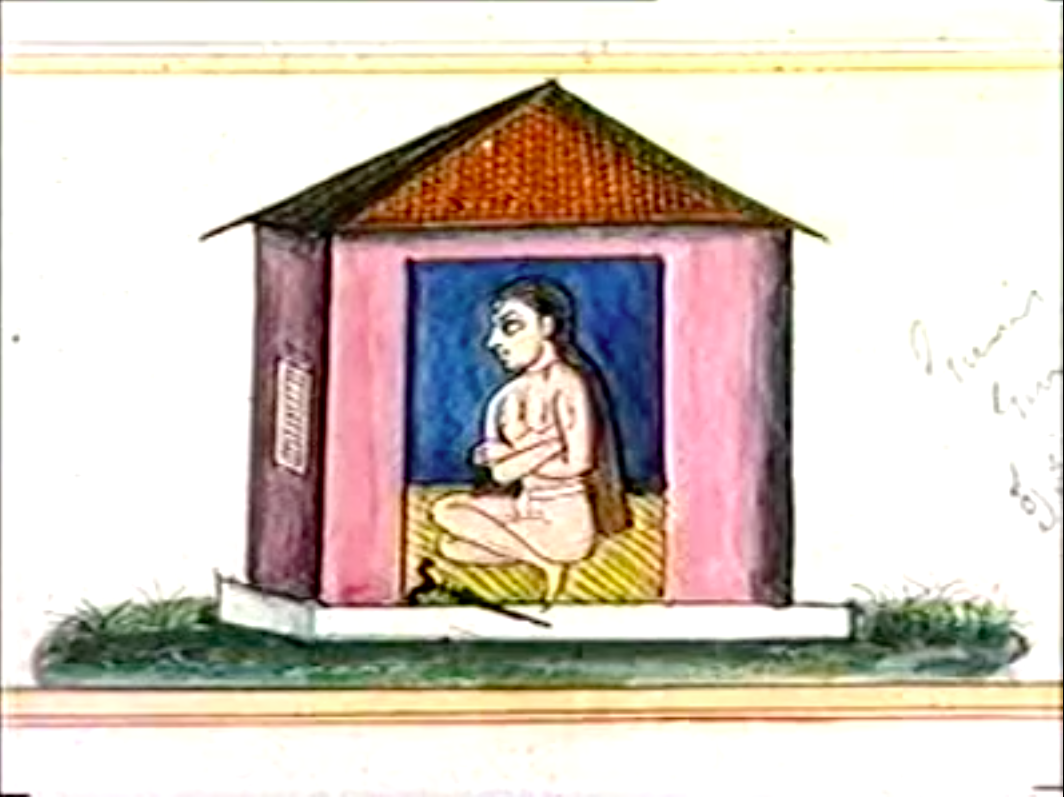

| Sure I've seen this picture elsewhere, the house isn't shown in the original, a child's imagination? |

In my post yesterday I embedded the documentary concerning Krishnamacharya's 100 year centenary celebrations. In the post I pick out a few highlights. One of them at 21:20

"...was of drawings said to be by Krishnamacharya's teacher in Tibet, Yogeshwara Ramamohana Brahmachari's daughter. I remember seeing two of these drawings in a Biography of Krishnamacrya, wonderful to see more of them. Isn't this a distinctive south Indian style of representation? Reminds me of those in Norman E. Sjoman, The Yoga Tradition of the Mysore Palace".

I couldn't resist following this up and doing a comparison of the pictures shown in the documentary and those in Norman's book taken from Sriitattvanidhi (1880s).

And they match up, the same images and yet slightly different, certainly more colourful, fresher, as if they had indeed been copied.

Sometimes, where pictures are placed together, they are in the same order as if (lets stick with the Ramamohana Brahmachari's daughter drawing them explanation) they had indeed been copied BUT from the/an original text, how did that come about?

I also checked and found that the four pictures (see towards thee end of the post) I had seen before in Krishnamachary's biography were different but that those pictures matched up with the original text also. This means that the book that Krishnamacharya supposedly brought back from Tibet has more pictures, one wonders how many, is it a complete copy of all the asana pictures in Sriitattvanidhi?

If the daughter story is true then Krishnamacharya had access to the book and we assume the text ( or his teachers teaching of the text) much earlier than Norman Sjoman suggests, in Tibet rather than Mysore.

Either that or perhaps Krishnamacharya copied the pictures himself in Mysore, a possibility.

I've always found these pictures to be dynamic, there is movement here, a vinyasa tradition perhaps?

I don't know what this all means for the history of modern postural practice but fascinating stuff, will need to have a think and chew on it a while.

I'll be teaching a Workshop on Krishnamacharya at StillPoint Yoga London this Sunday, perhaps we can discuss it at the end.

Norman Sjoman's book is essential reading if your interested in this work, Mark Singleton Yoga Body is heavenly indebted to Norman's text. As well as presenting the full text Norman translates all the instructions.

"The book (Yoga Tradition of the Mysore Palace) presents the first English translation of a part of kautuka nidhi; Sritattvanidhi, which includes instructions for and illustrations of 122 postures—making it by far the most elaborate text on asanas in existence before the twentieth century. The book includes instructions for 122 yoga poses, illustrated by stylized drawings of an Indian man in a topknot and loincloth. Most of these poses—which include handstands, backbends, foot-behind-the-head poses, Lotus variations, and rope exercises—are familiar to modern practitioners (although most of the Sanskrit names are different from the ones they are known by today). But they are far more elaborate than anything depicted in other pre-twentieth-century texts".

"The Sritattvanidhi (Śrītattvanidhi) ("The Illustrious Treasure of Realities") is an iconographic treatise written in the 19th century in Karnataka by the then Maharaja of Mysore, Krishnaraja Wodeyar III (b. 1794 - d. 1868). The Maharaja was a great patron of art and learning and was himself a scholar and writer. There are around 50 works ascribed to him.[1] The first page of the Sritattvanidhi attributes authorship of the work to the Maharaja himself:"

Wikipedia

|

| Keeps the legs comfortably together for meditation, Norman Sjoman discussed this on a recent workshop I took with him. |

From Sritattvanidhi (1800's) in Yoga tradition of the Mysore palace

How the pictures are presented in the 'original' Sritattvanidhi

And there's more.....

I mentioned that I had seen a couple of pictures that were supposed have been drawn by Krishnamacharya's teacher's daughter in a biography of Krishnamacharya. I remembered that I had posted them on a blog post and managed to find them, here they are in Sriitattvanidhi.

In Norman's book he names the asana and gives translations of the instructions/descriptions found above the pictures.

And YES, these too are in Sriitattvanidhi

A review of the argument in Norman's book from 2007

From Yoga Journal AUG 28, 2007

Previously Untold Yoga History Sheds New Light

BY ANNE CUSHMAN |

"The Mysore Palace

I found myself pondering these questions afresh recently after I came across a dense little book called The Yoga Tradition of the Mysore Palace by a Sanskrit scholar and hatha yoga student named Norman Sjoman. The book presents the first English translation of a yoga manual from the 1800s, which includes instructions for and illustrations of 122 postures—making it by far the most elaborate text on asanas in existence before the twentieth century. Entitled the Sritattvanidhi (pronounced “shree-tot-van-EE-dee”), the exquisitely illustrated manual was written by a prince in the Mysore Palace—a member of the same royal family that, a century later, would become the patron of yoga master Krishnamacharya and his world-famous students, B.K.S. Iyengar and Pattabhi Jois.

Sjoman first unearthed the Sritattvanidhi in the mid-1980s, as he was doing research in the private library of the Maharaja of Mysore. Dating from the early 1800s—the height of Mysore’s fame as a center of Indian arts, spirituality, and culture—the Sritattvanidhi was a compendium of classical information about a wide variety of subjects: deities, music, meditation, games, yoga, and natural history. It was compiled by Mummadi Krishnaraja Wodeyar, a renowned patron of education and the arts. Installed as a puppet Maharaja at age 5 by the British colonialists—and deposed by them for incompetence at the age of 36—Mummadi Krishnaraja Wodeyar devoted the rest of his life to studying and recording the classical wisdom of India.

At the time Sjoman discovered the manuscript, he had spent almost 20 years studying Sanskrit and Indian philosophy with pundits in Pune and Mysore. But his academic interests were balanced by years of study with hatha yoga masters Iyengar and Jois. As a yoga student, Sjoman was most intrigued by the section of the manuscript dealing with hatha yoga.

Sjoman knew that the Mysore Palace had long been a hub of yoga: Two of the most popular styles of yoga today—Iyengar and Ashtanga, whose precision and athleticism have profoundly influenced all contemporary yoga—have their roots there. From around 1930 until the late 1940s, the Maharaja of Mysore sponsored a yoga school in the palace, run by Krishnamacharya—and the young Iyengar and Jois were both among his students. The Maharaja funded Krishnamacharya and his yoga protégés to travel all over India giving yoga demonstrations, thereby encouraging an enormous popular revival of yoga. It was the Maharaja who paid for the now well-known 1930s film of Iyengar and Jois as teenagers demonstrating asanas—the earliest footage of yogis in action.

But as the Sritattvanidhi proves, the Mysore royal family’s enthusiasm for yoga went back at least a century earlier. The Sritattvanidhi includes instructions for 122 yoga poses, illustrated by stylized drawings of an Indian man in a topknot and loincloth. Most of these poses—which include handstands, backbends, foot-behind-the-head poses, Lotus variations, and rope exercises—are familiar to modern practitioners (although most of the Sanskrit names are different from the ones they are known by today). But they are far more elaborate than anything depicted in other pre-twentieth-century texts. The Sritattvanidhi, as Norman Sjoman instantly realized, was a missing link in the fragmented history of hatha yoga.

“This is the first textual evidence we have of a flourishing, well-developed asana system existing before the twentieth century—and in academic systems, textual evidence is what counts,” says Sjoman. “The manuscript points to tremendous yogic activity going on in that time period—and having that much textual documentation indicates a practice tradition at least 50 to 100 years older.”

Potpourri Lineage

Unlike earlier texts such as the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, the Sritattvanidhi doesn’t focus on the meditative or philosophical aspects of yoga; it doesn’t chart the nadis and chakras (the channels and hubs of subtle energy); it doesn’t teach Pranayama (breathing exercises) or bandhas (energy locks). It’s the first known yogic text devoted entirely to asana practice—a prototypical “yoga workout.”

Hatha yoga students may find this text of interest simply as a novelty—a relic of a “yoga boom” of two centuries ago. (Future generations may pore with equal fascination over “Buns of Steel” yoga videos.) But buried in Sjoman’s somewhat abstruse commentary are some claims that shed new light on the history of hatha yoga—and, in the process, may call into question some cherished myths.

According to Sjoman, the Sritattvanidhi—or the broader yoga tradition it reflects—appears to be one of the sources for the yoga techniques taught by Krishnamacharya and passed on by Iyengar and Jois. In fact, the manuscript is listed as a resource in the bibliography of Krishnamacharya’s very first book on yoga, which was published—under the patronage of the Maharaja of Mysore—in the early 1930s. The Sritattvanidhi depicts dozens of poses that are depicted in Light on Yoga and practiced as part of the Ashtanga vinyasa series, but that don’t show up in any older texts.

But while the Sritattvanidhi extends the written history of the asanas a hundred years further back than has previously been documented, it does not support the popular myth of a monolithic, unchanging tradition of yoga poses. Rather, Sjoman says that the yoga section of the Sritattvanidhi is itself clearly a compilation, drawing on techniques from a wide range of disparate traditions. In addition to variations on poses from earlier yogic texts, it includes such things as the rope exercises used by Indian wrestlers and the danda push-ups developed at the vyayamasalas, the indigenous Indian gymnasiums. (In the twentieth century, these push-ups begin to show up as Chaturanga Dandasana, part of the Sun Salutation). In the Sritattvanidhi, these physical techniques are for the first time given yogic names and symbolism and incorporated into the body of yogic knowledge. The text reflects a practice tradition that is dynamic, creative, and syncretistic, rather than fixed and static. It does not limit itself to the asana systems described in more ancient texts: Instead, it builds on them".

Fu;; article here http://www.yogajournal.com/article/philosophy/new-light-on-yoga/

I'll be presenting a workshop on Krishnamacharya StillPoint Yoga London next Sunday (still places)